Sidepath

A sidepath is a bidirectional shared use path located immediately adjacent and parallel to a roadway. Sidepaths can offer a high-quality experience for users of all ages and abilities as compared to on-roadway facilities in heavy traffic environments, allow for reduced roadway crossing distances, and maintain rural and small town community character.

Case

Study

Photo Gallery

Benefits

-

Completes networks where high-speed roads provide the only corridors available.

-

Provides a more appropriate facility for users of all ages and abilities than shoulders or mixed traffic facilities on roads with moderate or high traffic intensity.

-

Maintains rural character through reduced paved roadway width compared to a visually separated facility.

-

Fills gaps in networks of low-stress local routes such as shared use paths and bicycle boulevards.

-

Encourages bicycling and walking in areas where high-volume and high-speed motor vehicle traffic would otherwise discourage it.

-

Very supportive of rural character when combined with vegetation to visually and physically separate the sidepath from the roadway.

Considerations

-

Requires a wide roadside environment to provide for separation and pathway area outside of the adjacent roadway.

Geometric Design

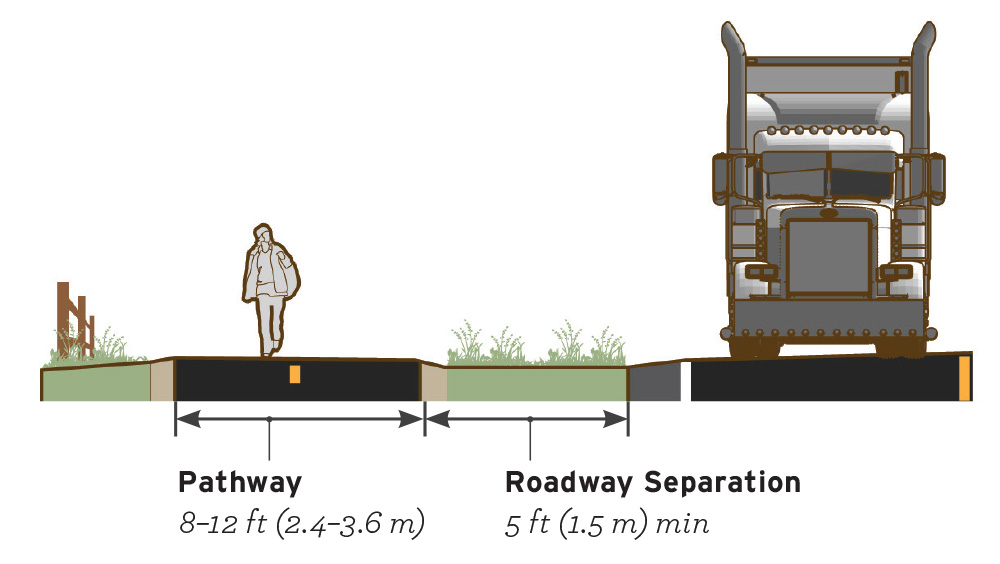

Widths and design details of sidepath elements may vary in response to the desire for increased user comfort and functionality, the available right-of-way, and the need to preserve natural resources.

PATHWAYSidepath width impacts user comfort and path capacity. As user volumes or the mix of modes increases, additional path width is necessary to maintain comfort and functionality.

- Minimum recommended pathway width is 10 ft (3.0 m). In low-volume situations and constrained conditions, the absolute minimum sidepath width is 8 ft (2.4 m)

- Provide a minimum of 2 ft (0.6 m) clearance to signposts or vertical elements.

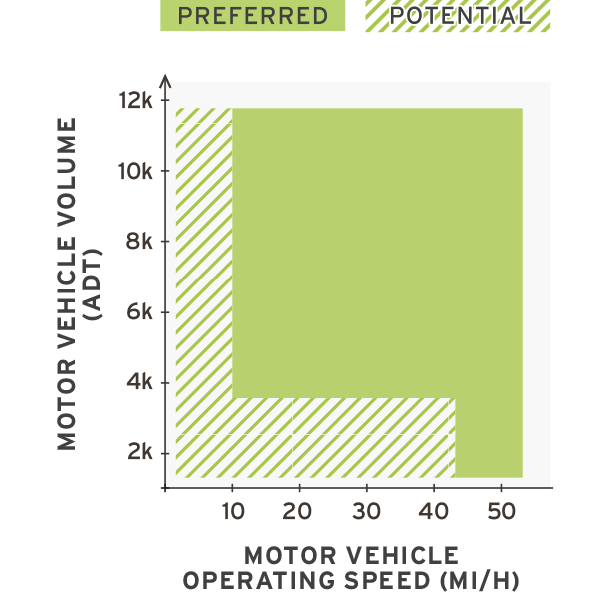

Separation from the roadway should be informed by the speed and configuration of the adjacent roadway and by available right-of-way as illustrated in Figure 4-9.

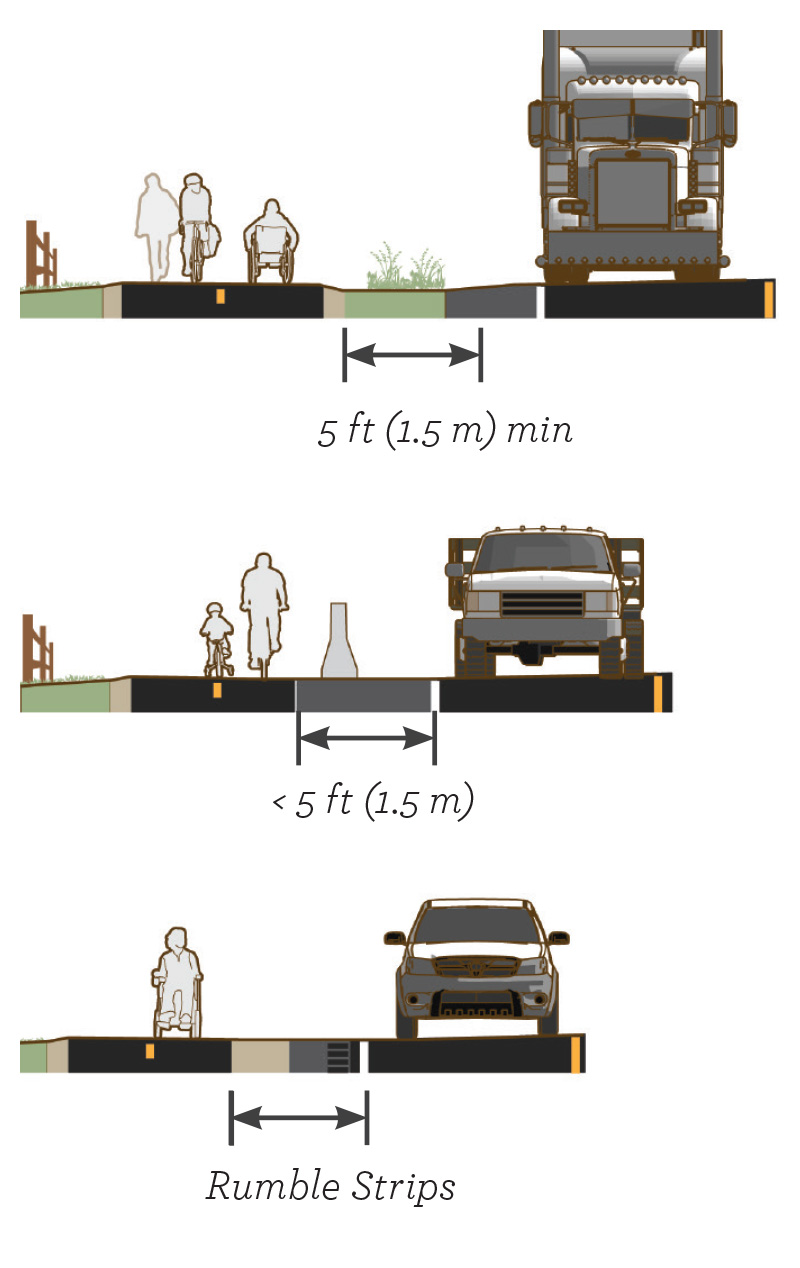

- Preferred minimum separation width is 6.5 ft (2.0 m). Minimum separation distance is 5 ft (1.5 m).

- Separation narrower than 5 ft is not recommended, although may be accommodated with the use of a physical barrier between the sidepath and the roadway. The barrier and end treatments should be crashworthy which may introduce additional complexity if there are frequent driveways and intersections. Refer to the AASHTO Roadside Design Guide 2011 for additional information.

Figure 4-9. Where a minimum of 5 ft (1.5 m) unpaved separation cannot be provided (top), a physical barrier may be used between the sidepath and the roadway (center). In extremely constrained conditions for short distances, on-roadway rumble strips may be used as a form of separation (bottom).

- On high-speed roadways, a separation width of 16.5–20 ft (5–6 m) is recommended for proper positioning at crossings and intersections.

Trees and landscaping can maintain community character and add value to the experience of using a sidepath. They provide shade for users during hot weather and help to absorb stormwater runoff.

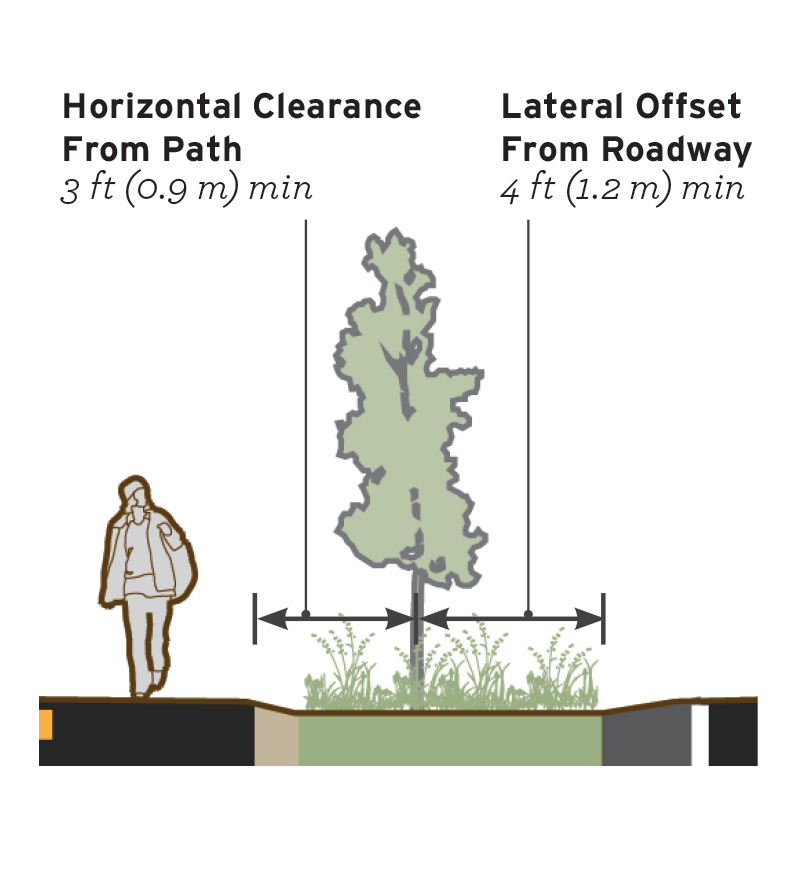

- Provide a 3 ft (0.9 m) horizontal clearance between trees and the pathway to minimize pavement cracking and heaving of the paved surface. Consult a local arborist in the selection and placement of trees.

- When trees are desired within the roadway separation area, consider planting small caliber trees with a maximum diameter of 4 inches (100 mm) to alleviate concerns about fixed objects or visual obstructions between the roadway and the pathway.

Figure 4-10. Even small trees can provide an additional feeling of separation between the sidepath and the roadway.

South Lake Tahoe, CA – Population 21,380

Tahoe Regional Planning Agency

Markings

Sidepaths may include edgelines or centerlines or be unmarked.

- Edge lines should be marked on paths expecting evening use.

- Paths with a high volume of bidirectional traffic should include a centerline. This can help communicate that users should expect traffic in both directions and encourage users to travel on the right and pass on the left (Flink and Searns 1993).

Signs

- Shared use paths are bidirectional facilities and signs should be posted for path users traveling in both directions.

- It is important for signs that only apply to the path to not be interpreted as a guidance for roadway travel lanes.

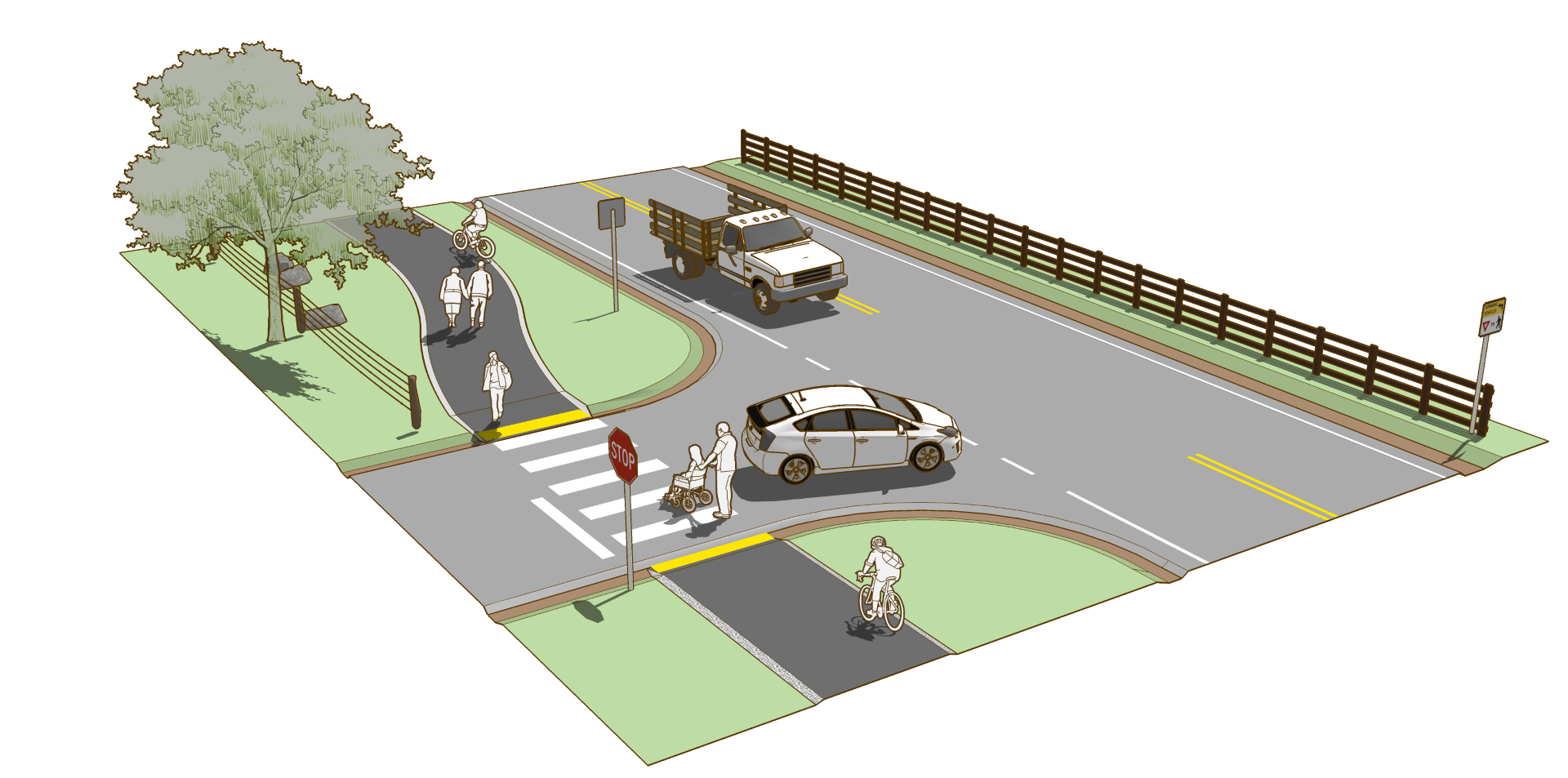

Intersections

Operational and safety concerns exist where sidepaths cross driveways and intersections. Refer to section 5.2.2 of the AASHTO Bike Guide 2012 for an identification of potential design issues. Design crossings to promote awareness of conflict points, and facilitate proper yielding of motorists to bicyclists and pedestrians.

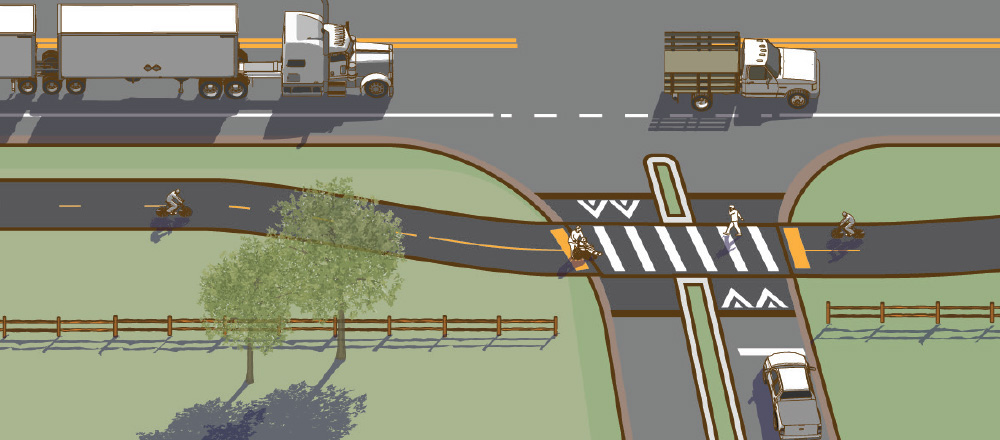

Design StrategiesCollision risk increases as the speed and volume of the parallel roadway increase. The AASHTO Bike Guide 2012 lists a variety of design strategies for enhancing sidepath crossings including:

- Reduce the frequency of driveways.

- Design intersections to reduce driver speeds and heighten awareness of path users.

- Encourage low speeds on pathway approaches.

- Maintain visibility for all users.

- Provide clear assignment of right-of- way with signs and markings and elevation change.

- Maintain physical separation of the sidepath through the crossing. Sidepath separation distance may vary from 5 ft–24 ft (1.5–7.0 m). Refer to Table 4-2.

- Use small roadway corner radii to enforce slow turning speeds of 20 mi/h or less. On a high-speed roadway, a deceleration lane may be necessary to achieve desired slow turning speeds.

- The roadway and path approaches to an intersection should always provide enough stopping sight distance to obey the established traffic control, and execute a stop before entering the intersection (AASHTO Bike Guide 2012).

- Configure crossings with raised speed table or “dustpan” style driveway geometry to create vertical deflection of turning vehicles. This physically indicates priority of path travel over turning or crossing traffic and helps reduce the risk associated with bidirectional sidepath use.

- Where possible, include raised median island on the cross street to provide additional safety and speed management benefits.

- Use crosswalk markings to indicate the through crossing along the pathway. Continental crosswalk markings are preferred for increased visibility. At low-volume residential driveways, crosswalk markings may be omitted.

- Use stop or yield line markings in advance of the crossing to discourage encroachment into the crosswalk area.

Figure 4-11. Separation distance should be selected in response to speed and traffic intensity. The pathway may need a shift in horizontal alignment in advance of the crossing to achieve desired separation distance. As speeds on the parallel roadway increase, so does the preference for wider separation distance.

Table 4-2. Sidepath Separation Distance at Road Crossings

*Separation distance may vary in response to available right of way, visibility constraints and the provision of a right turn deceleration lane.

Minor Street CrossingsGive sidepaths the same priority as the parallel roadway at all crossings. Attempts to require path users to yield or stop at each cross-street or driveway promote noncompliance and confusion, and are not effective. Geometric design in these cases should promote a high degree of yielding to path users through geometric design.

- Visual obstructions should be low to provide unobstructed sight of the crossing from the major street. Both motorists and path users should have a clear and unobstructed view of each other at intersections and driveways.

- Consider using a R10-15 RIGHT TURN YIELD TO PEDESTRIANS at street crossings with right turn interactions.

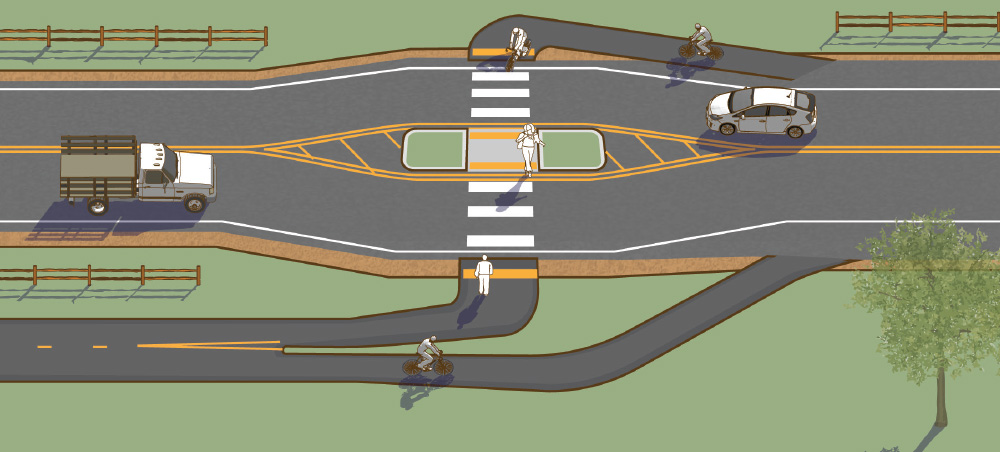

Where a sidepath terminates, it may be necessary for path users to transition to a facility on the opposite side of the road.

- Designs should consider the desire for natural directional flows, and the potential for conflicts with adjacent traffic. Use median islands and horizontal deflection of the roadway travel lanes to slow motor vehicle traffic and offer improved crossing conditions for path users.

Figure 4-12. Transition from a sidepath on one side to shoulders on each side of the road.

Accessibility

A sidepath is intended for use by pedestrians and must meet accessibility guidelines for walkways and curb transitions. Sidepaths are required to be accessible by all users, including those with mobility devices and visually-impaired pedestrians.

Implementation

Where sufficient roadway width or right of way is available, designers should consider the simultaneous provision of both sidepaths and bicycle accessible shoulders to serve a diverse range of user types.

Sidepath Case Study

Ennis, Montana

The Ennis schools are located in the heart of town, though there were few pedestrian and bicycle facilities connecting to them. In 2010, local nonprofit Madison Byways organized a program to identify safer routes to school.

The project resulted in a network of walking and biking facilities including a sidepath, sidewalks, and bicycle boulevards on residential streets. This network of facilities is called the Mustang Trail, named for the Ennis school mascot.

The central location of the schools means the bike and pedestrian network benefits the entire community, connecting neighborhoods to schools, businesses, and other services.

Critical factors for success included strong leadership by Madison Byways and a collaboration effort that engaged schools, residents, businesses, and public agency representatives. Numerous activities were held to increase awareness of the Mustang Trail, including monthly Farmer’s Markets, the 4th of July parade, and annual 5K run/walk.

Community Context

Rural destination community, especially in the summer, with a population of 880 in the town limits and 3,291 within the school district.

Key Design Elements

Sidepaths and sidewalks were constructed where previously there were no pedestrian facilities. The sidepath transitions from a concrete path in central Ennis to an asphalt path further west, toward a subdivision.

Role in the Network

The facilities connect neighborhoods to school and businesses throughout the community. In this small town, residential streets that connect neighborhoods to schools can be shared by people walking, biking, and driving.

Funding

Funded by grants from three Federal funding programs: Safe Routes to School (SRTS), Recreational Trails Program (RTP), and allocated through Madison County from the Community Transportation Enhancement Program (CTEP). Local fundraising provided matching funds for the grants.

For more information, refer to the City of Ennis.

Selected Examples

Works Cited

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD) Bridge Design Specifications. 2014.

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets. 2011.

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Roadside Design Guide. 2011.

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities. 2012.

CROW. Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic. 2006.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). An Overview and Recommendations of High-Visibility Crosswalk Markings Styles. 2013.

Flink, Charles, and Searns, Robert. Greenways: A Guide To Planning Design And Development. 1993.

Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT). Sidepath Facility Selection and Design. 2005.

Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Technical Committee 109-01. Pavement Marking Patterns Used at Uncontrolled Pedestrian Crossings. 2010.

Schepers et al. Road factors and bicycle—motor vehicle crashes at unsignalized priority intersections. Accident Analysis and Prevention. Volume 43, Issue 2, 2011.

Walker, A., Ryan, R. Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study. 2008.

Wachtel, Alan., Lewiston, Diana. Risk Factors for Bicycle-Motor Vehicle Collisions at Intersections. 1994.