Separated Bike Lane

A separated bike lane is a facility for exclusive use by bicyclists that is located within or directly adjacent to the roadway and is physically separated from motor vehicle traffic with a vertical element.

Case

Study

Application

Photo Gallery

Benefits

-

Provides a more comfortable experience on high-speed and high-volume roadways than on-road shoulders.

-

Offers an increased level of service over sidepaths in areas with high-volumes of pedestrians, when paired with sidewalks.

-

Increases the degree of connectivity over a sidepath, when configured as a one-way directional facility on both sides of the street.

-

Separated bike lanes offer bicyclists a similar riding experience to sidepaths but with fewer operational and safety concerns over bidirectional sidepath facilities.

-

Can reduce the incidence of sidewalk riding and potential user conflicts.

Considerations

-

Reflects a more urban visual atmosphere than a sidepath. Use of a wide landscaped buffer may lessen visual impact concerns.

-

Requires a wide roadside environment to provide for separation, sidewalks, and bike lane areas.

Design Guidance

Separated bike lanes can offer a similar experience as sidepaths for bicyclists and pedestrians but with increased functionality and safety where increased numbers of pedestrians and potential conflicts with motor vehicles are present. The guidance in this section focuses on one-way separated bike lanes. For two-way separated bike lanes, refer to the FHWA Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide 2015.

Russellville, AR – Population 28,581

Alta Planning + Design

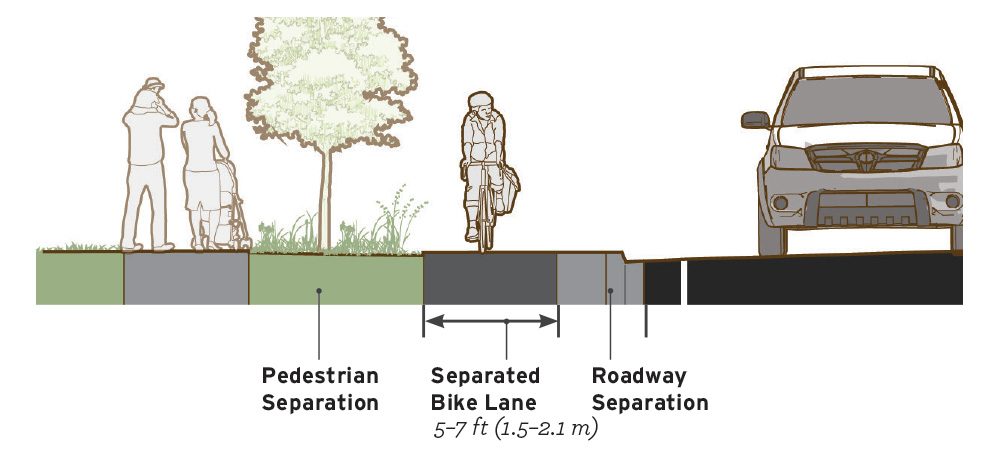

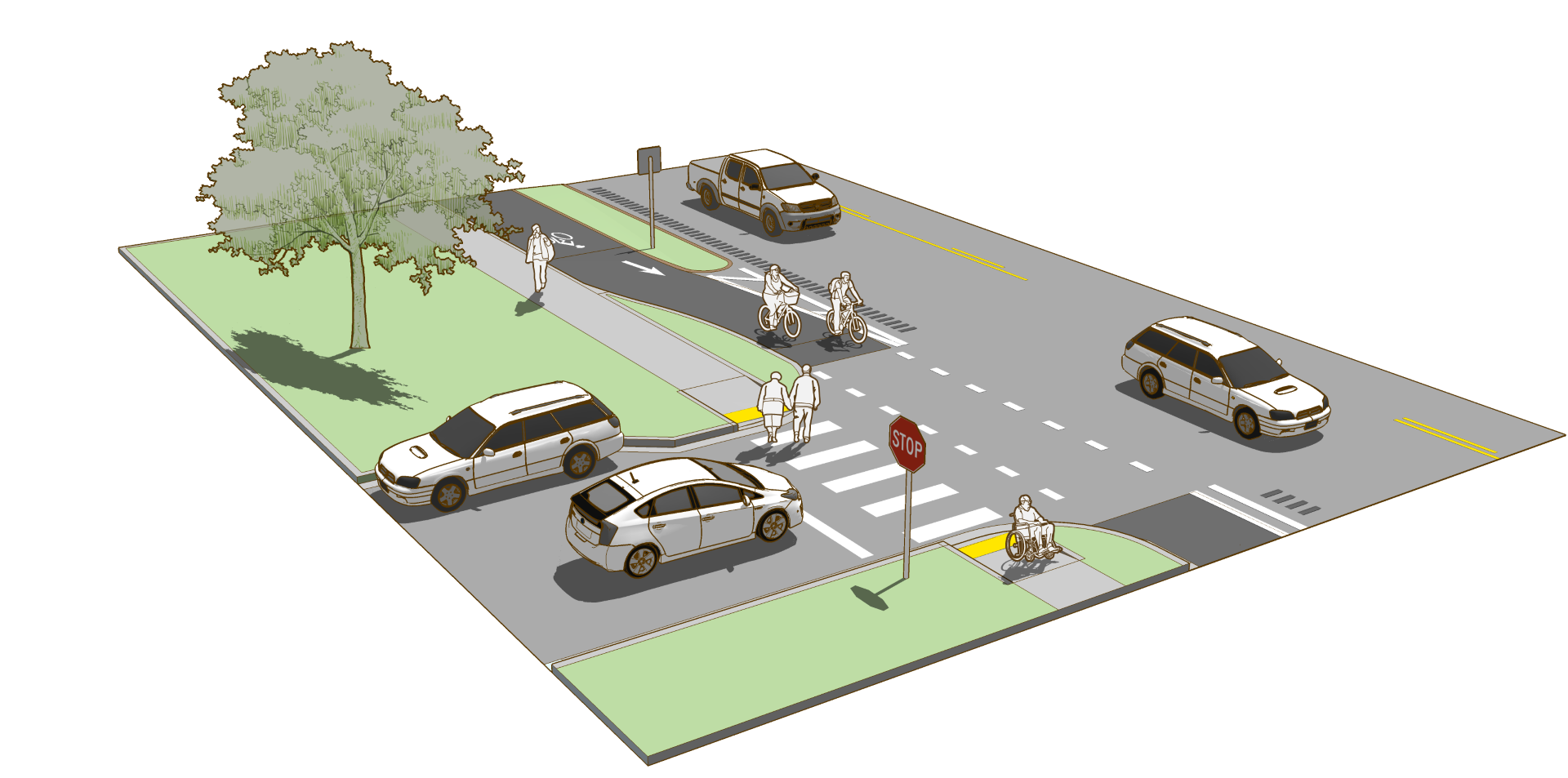

Figure 4-17. Separated bike lanes are exclusive facilities for bicyclists that are distinct from the sidewalk and physically separated from motor vehicle traffic with a vertical element.

Geometric Design

Separated bike lanes are made up of three interrelated zones, illustrated in Figure 4-17.

Separated Bike LaneThe separated bike lane zone offers a clear operating area for bicyclist travel. Because of the physical separation between the bike lane and the adjacent travel lanes, the design may be more sensitive to debris accumulation, maintenance access, and operating space impacts than conventional onstreet bike lanes.

- Preferred minimum width of a one-way separated bike lane is 7 ft (2.1 m). This width allows for side-by-side riding or passing.

- Absolute minimum bike lane width is 5 ft (1.5 m). At this width, bicyclists will not be able to pass slower users until there is a break in the facility and an opportunity to overtake.

- A clear through area of 10 ft (3.0 m) is beneficial for allowing access by snow plows and street sweepers.

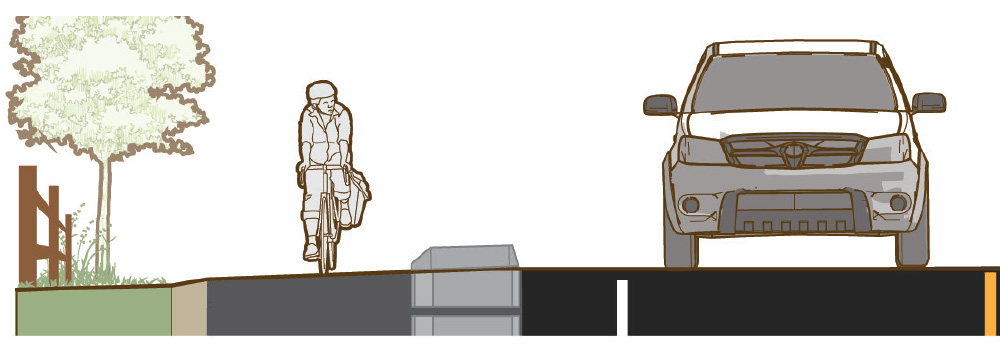

The roadway separation is the vertical element between the bike lane and the adjacent roadway. Separation width will vary based on separation type.

- A separation width of 3 ft (0.9 m) allows for a variety of separation methods and provides space adjacent to a parking lane to accommodate door swing and passenger unloading.

- A minimum width roadway separation of 1 ft (0.3 m) may be possible with a mountable or vertical curb face.

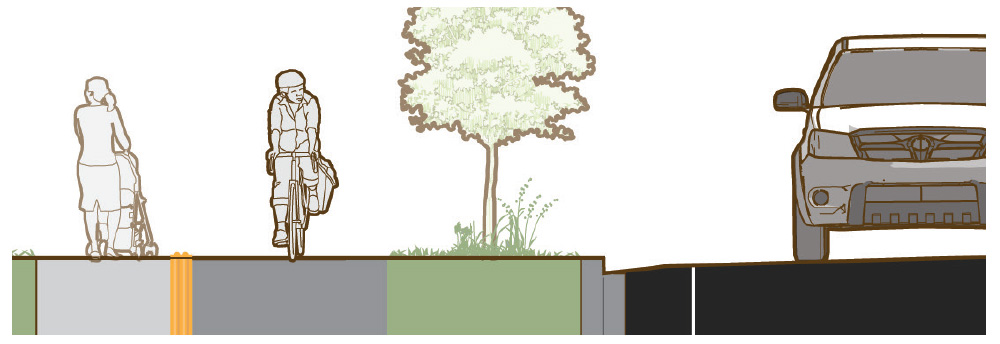

Separation from pedestrians is particularly important when a separated bike lane is located immediately adjacent and at the same level as a sidewalk.

- Design and construct separated bike lanes as clearly distinct from the sidewalk. This is accomplished with the use of a curb, separation buffer space, different pavement or other surface treatments, or detectable tactile guidance strips.

Jackson Hole, WY – Population 9,500

Wyoming Pathways

Figure 4-18. Separated bike lanes may be separated by an unpaved roadway separation, and a vertical element. When configured as directional facilities, separated bike lanes should be provided on both sides of the roadway.

Figure 4-19. Separated bike lanes may be configured on an existing roadway surface by using a physical barrier such as a curb or median to separate the bikeway from the roadway.

Figure 4-20. Separation from the sidewalk is valuable for reducing unwanted pedestrian encroachment into the bike lane. The use of physical separation with vertical elements, unpaved separation, or detectable edges may be more effective than visual delineation.

Marking

Separated bike lanes use markings to clarify intended users and travel direction.

- Standard Bike Lane symbol markings clarify that the lanes are for the exclusive use of bicyclists.

Signing

An optional Bike Lane (R3-17) sign may be used to supplement the bike lane pavement markings. Standards and guidance can be found in the MUTCD 2009.

Guide signs may be used to indicate which users belong on the separate parts of a separated bike lane corridor, as illustrated in Figure 4-21.

Figure 4-21. MUTCD signing options for specifying user types and path positioning can be used to indicate which users belong on the separate parts of a separated bike lane corridor (D11-1a, D11-2).

Intersections

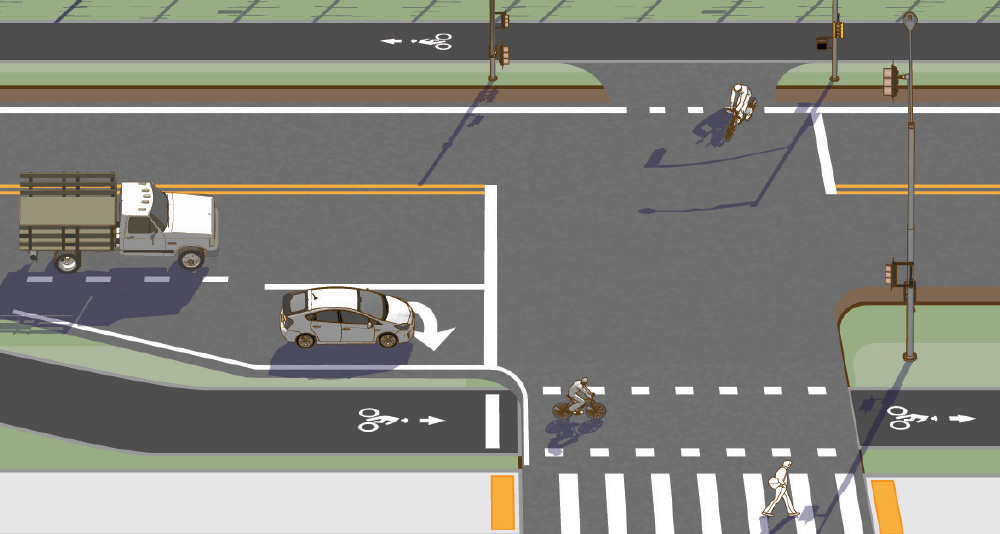

Separated bike lanes may operate similar to sidepaths at intersections, but the one-way directional alignment of the facility allows for additional design treatments and mitigates some of the operational and safety concerns associated with sidepath facilities.

Pedestrians should not travel within the separated bike lane. Accommodate pedestrians on a separate pedestrian facility such as a sidewalk.

Table 4-4 summarizes four approaches to treatments at intersections with separated bike lanes. For details on intersection treatments, refer to the FHWA Separated Bike Lane Guide 2015.

Under all conditions parking, if present, should be prohibited within 20 ft (6.0 m) of the intersection to improve visibility.

Missoula, MT – Population 69,100

Federal Highway Administration

Table 4-4. Intersection Treatments for Separated Bike Lanes

Position bicyclists closer to turning vehicles to increase visibility prior to the turn.

Provide space for right-turning vehicles to yield to bicyclists.

Shared turn lane with motor vehicles and bicyclists.

Separate conflicting movements in time.

Figure 4-22. A variety of design treatments exist depending on the roadway configuration, available curb-to-curb width, traffic volumes and desire to provided a dedicated turn lane. All designs should strive to reduce speeds of turning vehicles, remind users of bicycle priority, and clarify user positioning up to and through the intersection.

Implementation

With new roadway construction a raised separated bike lane can be less expensive to construct than adding an enhanced shoulder by building the separated bike lane to support reduced vehicle load requirements.

On streets with existing curb and gutter, it may be possible to implement a protected bike lane outside of the curb, between the curb and the sidewalk.

Separated bike lanes may be implemented during roadway resurfacing, rehabilitation, and reconstruction or new construction projects. For more information on implementation strategies, see the FHWA Resurfacing Guide 2016.

Accessibility

Separated bike lanes are not intended for use by pedestrians. On roadways with separated bike lanes, the appropriate pedestrian facility is a sidewalk.

The design of separated bike lanes must consider driveway conflicts, accessible parking and parking access aisles, transit stop access and egress, and loading zone accommodation (FHWA Separated Bike Lane Guide 2015).

Separated Bike Lane Case Study

Connellsville, Pennsylvania

The Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) is a long-distance trail network that connects Pittsburgh, PA with Washington, DC. The development of this network has taken grand vision and many years, with the first section of the trail being completed in 1986, and the final piece completed in 2013. The 150-mile trail connects defunct corridors of the four different railways. The Youghiogheny River Trail, as the section of the GAP through Connellsville is known, was constructed in the mid-1990s. During that time, Connellsville decided to route the trail along four blocks of South 3rd Street.

The roadway was widened without the need for additional right of way and the separated bike lane was created. The landscaped buffers are maintained by social groups and clubs in the community.

Because South 3rd Street is the connection of the GAP bike route through Connellsville, a critical aspect of the design is that the bike lane is bidirectional. Additionally, as this is the only section of the Passage that routes on city streets, the bike lane was separated to maintain the rider experience of being separated from motor vehicles. The landscaped buffer maintains this separation and encourages slowspeeds. Where the bike lane crosses West Crawford Avenue (State Route 711), a traffic signal was installed to improve safety at the intersection.

Community Context

Connellsville is a community of approximately 7,000, straddling the Youghiogheny River in western Pennsylvania’s Fayette County. Connellsville is located in the heart of coal country and was once a top producer of coke, the fuel for iron smelting furnaces. At one time, five different railways served Connellsville.

Key Design Elements

Vertically separated bike lane with curbs and planters providing physical separation.

Role in the Network

The separated bike lane is the connection of the GAP through Connellsville. Connellsville’s Bicycle Master Plan builds off of this key element in establishing a broader network that will connect people on bikes from the trail with businesses across the city and Connellsville residents with the GAP.

Funding

The South 3rd Street improvements were made through a local project with Federal funding for the signal improvement at West Crawford.

For more information, refer to the Connellsville Redevelopment Authority.

Selected Examples

Works Cited

Federal Highway Administration. Incorporating On-Road Bicycle Networks into Resurfacing Projects. 2016.

Federal Highway Administration. Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). Department of Transportation. 2009.

Federal Highway Administration. Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide. 2015.

Schepers, J.P., et al. Road factors and bicycle—motor vehicle crashes at unsignalized priority intersections. Accident Analysis and Prevention. Volume 43, Issue 2, 2011.